Yellowstone National Park: The World’s Most Unique and Scientifically Important National Park

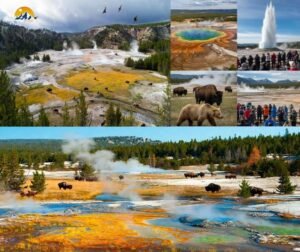

Hey buddy, when we talk about Yellowstone National Park, it’s not just a beautiful spot – it’s a living example of Earth’s inner forces at work. This is America’s first national park, and the oldest of its kind in the world. Everything here, from geysers and hot springs to volcanoes, animals, birds, and plants, shows nature’s incredible balance. Today, I’m giving you a full, fact-based, science-focused rundown, like a friend explaining it all over a cup of chai.

This post on junglejhadi.com is all about helping you understand that Yellowstone isn’t just a tourist place; it’s a living lab for science, geology, and ecology. Let’s cover everything from start to finish.

Yellowstone National Park Infobox

Category | Information |

|---|---|

Location | USA (Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho) |

Established | March 1, 1872 (The world’s first National Park) |

Area | Approximately 8,983 sq. km (2.2 million acres) |

Ecosystem Type | Temperate coniferous forest / Volcanic plateau |

Key Attraction 1 | Old Faithful (Famous predictable geyser) |

Key Attraction 2 | Grand Prismatic Spring (Largest hot spring in the U.S.) |

Geological Feature | Yellowstone Caldera (A massive supervolcano) |

Key Fauna (Animals) | Grizzly Bears, Wolves, American Bison, Elk, and Moose |

Unique Stat | Home to more than half of the world’s geothermal features (geysers/hot springs). |

UNESCO Status | Designated as a World Heritage Site in 1978 |

Best Time to Visit | June to August (Summer) or September to October (Fall) |

Yellowstone’s History and Establishment: The Beginning of Conservation

Friend, Yellowstone’s story kicks off in 1872, when on March 1st, the U.S. Congress made it the world’s first national park. President Ulysses S. Grant signed it into law. Imagine that era—people were cutting down forests and mining everywhere, ruining the land. But some forward-thinking folks said, “This place is so unique, we have to save it for everyone.” For more on the official establishment, check out the NPS Yellowstone History page.

Long before that, Native American unions like the Shoshone, Bannock, Crow, and Nez Perce lived here for thousands of years. They saw the hot springs as sacred and used them for healing. In the 19th century, white explorers arrived—like John Colter, who people called unbelievable for talking about “Colter’s Hell” because no one believed the geysers. Then the Washburn Expedition in 1870 reported the natural wonders, which led to the park’s creation.

In 1916, the National Park Service was formed to manage it. In 1978, UNESCO declared it a World Heritage Site, and in 1976, a Biosphere Reserve too. Remember the big 1988 fire? One-third of the park burned, but it was a natural process that brought new growth. All this shows Yellowstone was made for nature, not just for people.

Geology and the Supervolcano: What’s Happening Under the Ground?

Bro, Yellowstone’s real magic is in its geology. It’s sitting on a massive supervolcano—the Yellowstone Caldera—one of the world’s largest active volcanic systems. The last big eruption was 640,000 years ago, spreading ash across the U.S. There were two earlier massive ones—2.1 million and 1.3 million years ago. For detailed monitoring and facts, the USGS Yellowstone Volcano Observatory is the go-to source.

Today, there are over 10,000 hydrothermal features—geysers, hot springs, fumaroles, mud pots. Half the world’s geysers are here. Why? A magma chamber 3-8 km deep heats the water, building pressure until it erupts.

Norris Geyser Basin is the hottest, with temperatures up to 459°F. Steamboat Geyser is the tallest active one, sometimes shooting 300-400 feet. The USGS constantly monitors earthquakes, ground changes, and gas. No signs of a big eruption yet, but it’s active.

Old Faithful is the most famous—erupting every 60-90 minutes regularly. Grand Prismatic Spring is the third-largest hot spring in the world, with colors from bacteria and minerals—blue, green, orange, yellow.

Hydrothermal Features and Their Types

Yellowstone has four main types of hydrothermal features:

- Geysers: Explosive eruptions of water and steam. Old Faithful is famous, but Castle and Riverside are amazing too.

- Hot Springs: Constant flow of hot water. Grand Prismatic is the biggest and most colorful.

- Mud Pots: Bubbling hot mud with gases.

- Fumaroles: Just steam and gas venting out.

These are full of extremophile bacteria that live at 80-90°C. Scientists study them to understand how life began or if it exists on other planets.

Yellowstone’s Mammals: 67 Species in One Big Collection

Dude, Yellowstone has 67 mammal species—the highest concentration in the lower 48 states. It has a full predator-prey system with 8 ungulate species and 7 large predators. Check the official NPS Mammals page for the latest details.

- Bison: The biggest grazers, around 4,500-5,400 now. The world’s largest wild herd. They’re keystone species, shaping the ecosystem by grazing.

- Grizzly Bears and Black Bears: About 150-200 grizzlies in the park (over 1,000 in the greater ecosystem), and 500-600 black bears. Grizzlies have a hump and concave face.

- Wolves: Reintroduced in 1995, now around 95-110 in 8-10 packs. They control elk and balance everything.

- Elk: Most abundant large mammal, 10,000-20,000. Also called wapiti.

- Other Ungulates: Moose (under 500), Pronghorn (200-250), Bighorn Sheep, Mule Deer, White-tailed Deer, Mountain Goats (non-native).

- Smaller Ones: Beavers, coyotes, bobcats, river otters, badgers, foxes, wolverines, lynx, pika, hares, rodents, and 13 bat species.

Together, they keep the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem intact.

Yellowstone’s Birds: Nearly 300 Species in the Sky

Yar, nearly 300 bird species are recorded here, with about 150 nesting. Spring migration is the best time to see them. The NPS Birds page has great info on sightings.

- Raptors: Bald Eagles (along rivers and lakes), Golden Eagles, Ospreys, Peregrine Falcons.

- Waterfowl and Wetland Birds: Trumpeter Swans (biggest wild waterfowl, species of concern), Common Loons (southernmost breeding), Sandhill Cranes, American White Pelicans.

- Songbirds and Woodpeckers: The majority—Chickadees, Nuthatches, Warblers, Flycatchers, Thrushes, Jays, Ravens, Magpies.

- Year-round Residents: Common Raven, Canada Goose, Dusky Grouse, Black-billed Magpie, American Dipper, Mountain Chickadee.

Birds are key—spreading seeds, controlling insects, scavenging. Climate change affects migration and habitats.

Yellowstone’s Trees, Plants, and Vegetation: Over 1,300 Species

Brother, more than 1,300 native plant taxa here, including 1,150 flowering plants. Forests cover 80%, mostly lodgepole pine. Dive deeper into the NPS Plants page for full details.

- Conifers (9 species): Lodgepole Pine (80% of canopy), Whitebark Pine (high elevations, important for wildlife), Engelmann Spruce, Subalpine Fir, Douglas-fir (lower areas), Limber Pine, Rocky Mountain Juniper, Common Juniper.

- Deciduous Trees: Quaking Aspen (golden in fall), Cottonwood (along rivers), Willows.

- Shrubs: Sagebrush (many types, northern range), Rocky Mountain Maple, Common Juniper.

- Wildflowers: Hundreds—Phlox, Lupines, Cinquefoils, Larkspurs, Indian Paintbrush (Wyoming’s state flower), bright yellow ones like Oregon sunflower.

- Endemic Species (only here): Ross’s Bentgrass, Yellowstone Sand Verbena, Yellowstone Sulfur Wild Buckwheat (in thermal areas).

- Vegetation Communities: Lodgepole forests, Spruce-fir forests, Whitebark pine, Douglas-fir, Sagebrush-steppe, Wetlands, Hydrothermal (unique thermal plants).

Fire helps regeneration—lodgepole cones open with heat. Invasive plants are controlled.

Scientific Importance and Research in Yellowstone National Park

Yar, Yellowstone National Park is truly a science heaven—a massive, living natural laboratory where researchers from around the world come to study everything from the deepest Earth processes to the tiniest microbes that can change our everyday lives. Yellowstone issues between 150 and 200 research permits annually—one of the highest volumes in the entire National Park Service system. Scientists conduct studies ranging from huge landscape-level ecosystem changes to microscopic organisms with global impacts.

This makes Yellowstone not just a protected wilderness, but a key site for understanding how our planet works, especially in an era of climate change and volcanic activity. For more on conducting research here, check the official NPS Research page.

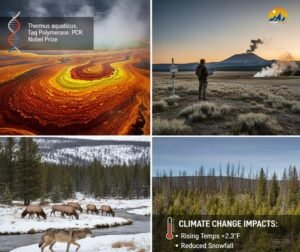

The most famous scientific breakthrough from Yellowstone is the discovery of Thermus aquaticus (T. aquaticus), a thermophilic bacterium found in the hot springs (like Octopus Hot Spring) in the 1960s by microbiologist Thomas Brock and his team. This extremophile thrives in temperatures up to 80°C (176°F) or more, producing a heat-stable enzyme called Taq polymerase. In the 1980s, Kary Mullis used this enzyme to invent the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) technique, which amplifies DNA quickly and reliably.

Without Taq polymerase, modern biotech wouldn’t have advanced so fast—PCR is the backbone of genetic testing, forensics, disease diagnosis, and even the COVID-19 PCR tests (some named TaqPath after it!) that helped the world fight the pandemic. Mullis won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1993 for this work. It’s no exaggeration to say this one microbe from Yellowstone’s hot pools revolutionized medicine and biology worldwide.

Yellowstone’s extremophiles (heat-loving microbes like thermophilic Archaea, Bacteria, Eukarya, and even viruses) continue to be studied for insights into life’s origins on Earth and potential life on other planets, as NASA and astrobiologists look at similar harsh environments. Dive deeper into this on the NPS article about thermophiles or the USGS story on how Yellowstone bacteria helped fight COVID-19.

Then there’s the volcanic and geological research, led by the USGS Yellowstone Volcano Observatory (YVO)—a consortium of nine agencies including USGS, universities, and state geological surveys. YVO constantly monitors the supervolcano with a huge network of instruments: seismometers for earthquakes (hundreds of small ones happen yearly, mostly magnitude 2-3, which is normal), GPS and tiltmeters for ground deformation, gas sensors, infrasound for hydrothermal explosions, and satellite data.

They track the magma chamber, hydrothermal systems, and potential hazards. Recent highlights include the first instrumentally detected hydrothermal explosion on April 15, 2024, in Norris Geyser Basin (detected via seismic and infrasound sensors), studies on magmatic volatiles, lithium deposits from ancient hotspot activity, and ongoing deformation patterns (like seasonal uplift in the caldera).

The observatory issues monthly updates, and the current status is NORMAL with no signs of imminent big eruption. This monitoring is crucial because Yellowstone is classified as a high-threat volcano, and understanding it prevents panic while providing real data on Earth’s inner dynamics. Stay updated with the YVO official site and their volcano updates.

On the ecology and climate change front, Yellowstone serves as a model for how intact ecosystems respond to warming. The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE) is one of North America’s last nearly untouched temperate zones, and researchers track shifts: average temperatures have risen 2.3°F since 1950 (potentially +5-10°F by 2100), reduced snowfall, earlier snowmelt, more droughts, increased wildfires, and impacts on whitebark pine (threatened by beetles due to warmer winters), bison migrations, wolf-elk dynamics (from the famous 1995 wolf reintroduction), cutthroat trout, wetlands, and amphibians. Long-term data from lake sediments (like Yellowstone Lake cores) reveal how past climates affected vegetation, fire regimes, and diatoms, helping predict future changes.

The 2021 Greater Yellowstone Climate Assessment (a collaboration between USGS, Montana State University, University of Wyoming, and others) highlighted ecosystem-wide threats like water scarcity, biodiversity loss, and shifts in forests and rivers, guiding adaptation strategies for wildlife and surrounding communities. Check the NPS Climate Change page for details on changes in the park.

Overall, Yellowstone’s research connects dots across disciplines—geology, microbiology, ecology, climatology—and contributes to global knowledge. From Nobel-winning biotech to volcano safety and climate insights, this park shows why protecting natural labs is vital. It teaches us about resilience, change, and our place on this dynamic planet.

Why Yellowstone is So Special

Yar, Yellowstone isn’t just a park—it’s the heart of the Earth. The supervolcano, geysers, mammals, birds, plants—all together show how powerful and delicate nature is. It teaches us conservation is essential. Whether you visit or just read, you’ll realize we’re just guests on this planet.

More info posts like this coming on junglejhadi.com. If you want more details, just say. Overall, this place is the perfect mix of science and wonder.

Yellowstone National Park – Frequently Asked Questions

- Read this – Sanjay Gandhi National Park : Its Geography, Biodiversity, Wildlife

- Kanha National Park : explore its history, geography, flora, fauna

Q1. Why is Yellowstone National Park so famous?

Buddy, Yellowstone is famous because it’s the world’s first national park and one of the most geologically active places on Earth. Geysers, hot springs, a supervolcano, wildlife, forests—everything comes together here. It’s not just a tourist destination, it’s a real-life science classroom.

Q2. Does Yellowstone really sit on a supervolcano?

Yes, absolutely. Yellowstone sits on a massive supervolcano. The last major eruption happened about 640,000 years ago. Magma is still active underground, but according to scientists, there is no immediate danger. The system is active, not erupting.

Q3. Will Yellowstone erupt again in the future?

Simple answer: someday, but not anytime soon. On a geological time scale, eruptions are rare events. Scientists monitor Yellowstone 24/7, and right now there are no signs of a major eruption coming soon.

Q4. Why is Old Faithful geyser so special?

Old Faithful is special because it erupts regularly, roughly every 60–90 minutes. Geysers themselves are rare worldwide, and a predictable one like Old Faithful is even rarer. That’s why it’s a favorite for both visitors and scientists.

Q5. Why does Yellowstone have so many geysers?

The secret is heat + water + underground plumbing. Magma heats groundwater, pressure builds up, and hot water explodes to the surface as geysers. That’s why Yellowstone has more than half of the world’s geysers.

Q6. Did Yellowstone bacteria really help modern science?

Yes, and in a huge way. A bacterium called Thermus aquaticus was discovered here. It led to the invention of PCR testing, which is used in DNA analysis, crime investigations, medical diagnostics, and COVID-19 tests. One tiny microbe from Yellowstone changed the world.

Q7. Why are Yellowstone’s animals so important?

Yellowstone has a complete ecosystem—predators and prey living together naturally. Wolves, bears, bison, and elk maintain balance. After wolves were reintroduced in 1995, rivers, forests, and wildlife behavior all changed. Scientists still study this today.

Q8. Are bison really that important in Yellowstone?

Definitely. Yellowstone has the largest free-roaming bison herd in the world, around 4,500–5,400 animals. Bison are a keystone species—their grazing keeps grasslands healthy and supports other wildlife.

Q9. How is climate change affecting Yellowstone?

Temperatures are rising, snowfall is decreasing, wildfires are becoming more intense, and ecosystems are shifting. Trees like whitebark pine are under threat, and animal migration patterns are changing. Yellowstone gives scientists a clear picture of what climate change looks like in action.

Q10. Is Yellowstone still natural, or is it heavily controlled by humans?

Yellowstone remains mostly natural. Park managers focus on letting natural processes—fires, floods, predators—do their job, while humans step back and observe rather than control.

Q11. Can visitors walk close to geysers and hot springs?

Only on designated boardwalks. Going off-trail is dangerous and illegal. The ground can be thin, with boiling water just below the surface. Every year, accidents happen when people ignore the rules.

Q12. Why is Yellowstone called a “living laboratory”?

Because scientists study geology, biology, climate change, volcanoes, and microbes—all in one place. Data from Yellowstone helps researchers understand Earth’s past and predict future changes.

Q13. Why is Yellowstone important for the future?

Yellowstone helps us understand how Earth systems work and how to protect them. It’s not just America’s treasure—it’s a global natural heritage that benefits all of humanity.

Q14. Is Yellowstone just a place to visit, or something more?

It’s much more than a sightseeing spot. Yellowstone teaches us that humans are guests on this planet, not owners. Respecting nature is the only way to ensure a safe future.