Jhelum River : The Lifeline of Kashmir – A Comprehensive Journey from Origin to Sea

The Jhelum River, known as the “Vitasta” in Sanskrit, “Vyeth” in Kashmiri, and “Hydaspes” in Greek, is one of the most significant rivers in South Asia. As the westernmost of the five rivers of the Punjab region, it flows through India and Pakistan, shaping the geography, culture, and economy of the regions it traverses. This post takes you on a detailed journey of the Jhelum River, from its origin at Verinag Spring to its confluence with the Arabian Sea, while also exploring its historical, cultural, and environmental significance.

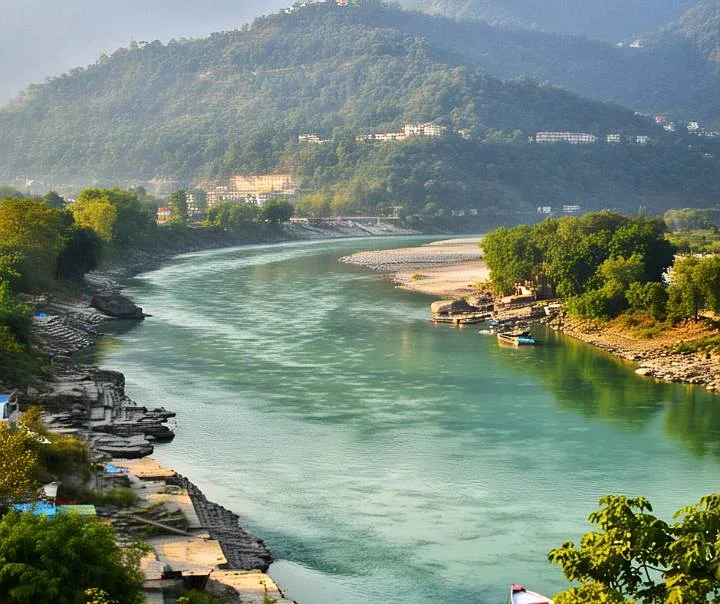

1. Origin of the Jhelum River

The Jhelum River originates from the Verinag Spring, a deep blue spring located at the foothills of the Pir Panjal Range in the Anantnag district of Jammu and Kashmir, India. Situated at an elevation of approximately 1,876 meters above sea level, Verinag is considered a sacred site, and its serene beauty attracts tourists and pilgrims alike. According to Hindu mythology, the river is associated with Goddess Parvati, who emerged from the netherworld at Verinag when Lord Shiva struck the ground with his spear, naming the river Vitasta [].

The spring is surrounded by a Mughal-era garden, commissioned by Emperor Jahangir, adding historical charm to the site. From Verinag, the Jhelum begins its 725-kilometer (450-mile) journey, initially flowing northwestward through the picturesque Kashmir Valley [].

Verinag Spring – Jammu & Kashmir Tourism

2. Course Through the Kashmir Valley

As the Jhelum flows through the Kashmir Valley, it meanders through lush landscapes, shaping the region’s geography and supporting its agrarian economy. The river passes through key towns like Anantnag and Srinagar, the summer capital of Jammu and Kashmir. In Srinagar, the Jhelum bifurcates the city into two parts and is fed by the waters of Dal Lake, a famous tourist destination [].

The river then enters Wular Lake, one of the largest freshwater lakes in India, located near Srinagar. Wular Lake acts as a natural regulator of the Jhelum’s flow, preventing floods during the monsoon season and maintaining water levels during dry periods. Emerging from Wular Lake, the river flows westward, cutting through the Pir Panjal Range via a deep gorge near Baramulla, with depths reaching up to 7,000 feet (2,100 meters) [].

Tributaries in the Kashmir Valley:

- Lidder River: Joins the Jhelum near Khannabal, fed by glaciers from the high Himalayan ranges.

- Sindh River: Originates near the Haramukh Mount and merges with the Jhelum at Shadipora.

- Other smaller tributaries include Sandran, Bringi, Arapath, Vishow, and Rambiara [].

Wular Lake – Ecological Significance

3. Jhelum River enters Pakistan

After passing through Baramulla and Uri, the Jhelum enters a narrow gorge and crosses the Line of Control (LoC), flowing into Pakistan Occupied Kashmir. At Muzaffarabad, the administrative center of Pakistan Occupied Kashmir, the Jhelum is joined by its largest tributary, the Kishanganga River (also known as the Neelum River), followed by the Kunhar River from the Kaghan Valley. These tributaries significantly increase the river’s flow [].

The river then bends southward, forming part of the border between Pakistan Occupied Kashmir and Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. Near Mangla, the Jhelum breaks through the Outer Himalayas, forming broad alluvial plains. It flows into the Mangla Dam Reservoir, a major multipurpose dam in Pakistan’s Mirpur District, which supports irrigation and hydroelectric power generation [].

Mangla Dam – Pakistan Water and Power Development Authority

4. Journey Through Punjab and Confluence

In Pakistan’s Punjab province, the Jhelum flows through the Jhelum District, forming the boundary between the Jech and Sindh Sagar Doabs. The river passes through cities like Jhelum and Khushab, turning southwestward along the Salt Range. It eventually joins the Chenab River near Trimmu in the Jhang District [].

The combined waters of the Jhelum and Chenab form the Panjnad River, which merges with the Sutlej River before joining the Indus River at Mithankot. The Indus River, carrying the waters of the Jhelum, ultimately empties into the Arabian Sea south of Karachi, completing the Jhelum’s journey from its Himalayan origin to the sea [].

5. Hydrological and Environmental Aspects

The Jhelum River’s hydrology is influenced by snowmelt from the Karakoram and Himalayan ranges in spring and the southwest monsoon from June to September. Peak flood discharges can exceed 1,000,000 cubic feet per second, while winter flows are significantly lower []. However, environmental challenges threaten the river’s health:

- Pollution: Industrial estates and untreated wastewater from urban areas, including Srinagar, degrade water quality. Lakes like Dal and Wular suffer from eutrophication due to fertilizer runoff [].

- Climate Change: Rising temperatures and reduced snowfall in the Himalayas have decreased glacier volume in the Jhelum basin by 27.47% between 1962 and 2013, impacting water availability [].

- Microplastics: Studies have detected high concentrations of microplastics in the Jhelum, particularly downstream of municipal waste disposal sites [].

Environmental Challenges of Jhelum River – SANDRP

6. Historical and Cultural Significance

The Jhelum River has been a cradle of civilization and a witness to significant historical events:

- Ancient Names and Mythology: Known as Vitasta in the Rigveda and Nilamata Purana, the river is revered in Hindu mythology as a manifestation of Goddess Parvati. The ancient Greeks called it Hydaspes, and it was mentioned by historians like Arrian and Ptolemy [].

- Battle of Hydaspes (326 BCE): Alexander the Great defeated King Porus on the banks of the Jhelum, marking a significant moment in ancient history. Alexander founded the city of Bukephala (near modern-day Jalalpur Sharif) to honor his horse, Bucephalus [].

- Mughal Era: The Jhelum was a vital transportation route during the Mughal period, and Emperor Jahangir developed the Verinag garden [].

- Indus Waters Treaty (1960): This treaty between India and Pakistan allocates the Jhelum’s waters primarily to Pakistan, with India permitted limited use for agriculture and hydropower [].

Indus Waters Treaty – World Bank

7. Economic and Strategic Importance

The Jhelum River is a lifeline for the regions it serves:

- Irrigation: The Upper Jhelum Canal and Lower Jhelum Canal irrigate millions of acres in Pakistan’s Punjab province. The Mangla Dam alone irrigates about 3 million acres [].

- Hydropower: The river supports significant hydroelectric projects, including the Uri Dam (480 MW) in India and the Mangla Dam (1,000 MW) in Pakistan. India is also developing projects on tributaries like the Kishanganga to establish water rights under the Indus Waters Treaty [].

- Tourism: The Jhelum’s scenic beauty, especially in the Kashmir Valley, attracts tourists to places like Srinagar, Dal Lake, and Verinag [].

Uri Dam – National Hydroelectric Power Corporation

8. Challenges and the Way Forward

The Jhelum River faces several challenges that require sustainable solutions:

- Water Scarcity: Reduced snowmelt and glacier depletion threaten water availability, particularly in autumn [].

- Sinkholes and Geological Risks: In 2022, a sinkhole in the Brengi stream, a Jhelum tributary, disrupted water supplies and caused ecological damage [].

- International Cooperation: The Jhelum’s transboundary nature necessitates collaboration between India and Pakistan to manage water resources effectively under the Indus Waters Treaty [].

Sustainable practices, such as stricter pollution control, afforestation in the catchment area, and climate-resilient infrastructure, are essential to preserve the Jhelum’s vitality.

Sustainable Water Management – United Nations

Conclusion

The Jhelum River is more than just a waterway; it is a symbol of life, history, and resilience in the regions it nurtures. From its tranquil origin at Verinag Spring to its mighty confluence with the Arabian Sea, the Jhelum shapes landscapes, sustains economies, and carries the stories of ancient civilizations and modern nations. By addressing its environmental and geopolitical challenges, we can ensure that this lifeline continues to flow for generations to come.

Explore More:

- Most Dangerous Animals in the Jungle | Top 10 Dangerous Animals

- Ganga River : lifeline of Indian culture, spirituality, and economy